The Journey Begins.

It was almost precisely 30 years ago today that my journey into the world of computing began. I remember the day that my parents bought the Sinclair ZX81 which was to become my Christmas present, we’d gone to Bedford to buy it in W.H.Smiths and it came in a brown cardboard box with nothing printed on the outside. We’d then all got into the car and whilst we drove up past St. Neots towards some shop on the Cambridge road I was able to open the box and start to read the manual. (We didn’t find the shop in the end and I can’t remember what it was supposed to be selling. Instead we turned back at a small roundabout and drove home.)

At the time I thought of computers as literally magical things. I’d seen them on “Tomorrow’s World” where a year or so before they were extolling the new technology which now cost less than a thousand pounds (showing the TI 44/9). Other than this I’d only seen computers on “Horizon” or in science fiction but here, now was one sitting in a small box on the back seat of my parents’ car beside me. I also marvelled at the ZX81 manual with its painting of a science fiction inspired landscape. (Why are computer manuals so much more boring these days?)

As for programming, at this time I’d only overheard conversations from my class mates at my new school who had had some lessons in the science block. They talked of mystical incantations and something to do with “print, print, print.”

Of course, this being a Christmas present, once we got home it was put away in a top cupboard, out of sight. But still, that was the beginning of the journey.

One Small Computer For A Man…

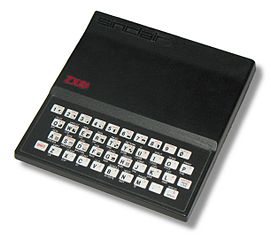

And so, Christmas Day came and I was at last able to get my hands on the ZX81. It was set up on a chrome steel and glass coffee table and connected to our old “Elizabethan” 12″ black and white portable TV which we’d used in the caravan on holiday. I already had a “Binatone” cassette recorder, which I remember getting for my birthday in ’77, but at this point it wasn’t able to be used as I had no tapes with software on. However, the Christmas of 1981 was spent cross-legged tapping at the flat plastic membrane keyboard typing in the examples from the manual.

It wasn’t long, however, until I soon hit the limit of the 1K memory, so my progress stalled for a while. It wasn’t until my birthday in February that I managed to get the 16K RAM Pack. Wow! How could anyone fill a whole 16K?! Well, I certainly couldn’t.

Anyway, at this point I think I should start compressing the time scales otherwise this post will become a book. Suffice it to say that the ZX81 was my mainstay computer for a further 15 months and it taught me the basics. It also taught me how to be patient after spending one and a half days typing in hex code out of the “Your Computer” magazine only for a thunderstorm to wipe out my work. A further two days of typing later and a rudimentary “Space Invaders” game was ready to play, which worked for about a minute until it crashed due to a typo somewhere in the pages of code.

The Steady March of Progress.

In the May of 1983 I finally persuaded my Dad to help me buy a replacement computer, a ZX Spectrum 16K. At the time this cost a huge amount, £125. Well, at the time £125 WAS a lot of money, at least for my family. Of course, the timing was awful as only a couple of weeks later Sinclair dropped the price of the Spectrum so that £125 would get your the 48K model. Later in the year I sold the ZX81 to one of my Dad’s work mates so I could buy a Fox Electronics 48K upgrade as many of the games I wanted to play by now required the larger memory. (Can you remember when games were all £4.99? Wasn’t it a scandal when they suddenly jumped to about £6 a pop?! :-)) I later bought the ZX81 back from the person I sold it to for a profit and it’s now in my loft.

The Speccy was the machine upon which I did most of my first real world work. This was helped by the addition of the Interface 1 and ZX Microdrives in the summer of ’84 along with the first printer, a Brother HR-5 thermal ribbon printer which could output at an amazing 30 characters per second. This combination took me right through to half way through my degree, upon which I wrote most of my essays using the “Tasword 2” word processor.

During this period I made my first computer purchase mistake. During the latter months of 1984 I had been reading “Your Computer” magazine and getting more and more enthused about the Memotech MTX series machines. They were sleek (for the time) and they even professed to have a ZX Spectrum emulator in the works. Best of all, they had a built in debugger/assembler/disassembler on board just like the “professional” RML 380Z I’d seen and used at school. How could it be bad?

So, after saving up my student grant (yes, they were magical things too) by basically not having a social life in the first term at Uni. (this wasn’t a concious decision) I spent £199 on a MTX500. This was a very bad move. The machine itself was OK, but being basically an MSX machine but without the compatibility and software being expensive and hard to come by it was a bit of a lemon. The Spectrum still got more use.

And On, Into The Future.

In the January of 1986 I managed to convince my Mum that I needed something more capable to do my University work upon and so along came the Sinclair QL.

This was a major leap forward. Not only did it come with a full office suite of programs, including a word processor, spreadsheet and database application, but it also had a procedural BASIC programming language and pre-emptive multitasking. i.e. Welcome to the modern world.

Suffice it to say that this machine was invaluable for my University work, not only as a word processor upon which I wrote my degree mapping project report (I won’t go into the story of the power cut in the halls as I was writing the conclusions) but it was also used to write programs to do some of the project work, such as normative mineral analysis and plotting up data for the remote sensing coursework.

It was also the machine which really got me into low level programming and assembler. QDOS is/was a beautiful and simple operating system to code assembler on and Motorola M68000 assembler is really quite high level, the combination of which made it simple to write programs. The high-water mark of which, for me, was a full emulation of the University College London BBC Micro terminal emulator engineered from their documentation. It was a combination of a DEC VT52 emulator and a Tektronix T4010 graphics terminal emulator with access to the BBC’s *FX commands.

The QL also acted as a my development machine for many projects during my MSc in Computer Science, especially those involving assembly coding. In a way, this is THE machine I learnt the most from.

Onwards and upwards.

I’m now going to speed up a gear and skim past my first floppy disk drive in ’87, the second hand BBC Micro to play Elite in the December of the same year and even the Atari 520STM in the summer of ’88. No, the next “big thing” was the first hard disk drive in 1989.

It was a revolution! You could store huge amounts! It was fast! It was expensive! Wow!

Actually, other than the first and statements these would seem laughable today. The device was a 28MB drive for the Atari ST and cost a whopping £400. In today’s money you should probably at least double that figure. Today 28MB would seem like a pitifully tiny amount of storage, enough to hold a couple of images taken with a digital camera, but it seemed cavernous. This was helped by the fact that the ST could only use a modified version of the FAT12 file system and the hard disk drivers could only use disk partitions up to 4MB in size!

Oh, and as for the the statement, “it was fast”, well all things are relative. There was a disk speed testing program which came with the disk utilities which could measure the sped of your drive. Bear in mind that this drive was a Seagate SCSI device… the maximum read speed was about 600K/s and writes maxed out at about 400K/s! Today I am getting similar speeds from my ADSL connection and I’m not that close to the exchange.

The Technological Slow Down.

Up until now it seemed that every year brought a new wonder. Indeed, with the arrival of first Minix and then MiNT on the Atari ST and TT030, I was getting closer and closer to having a UNIX box in the house.

Actually, in 1993 I picked up a Sun 3/80 via Alec Muffett and then purchased for about £500 a Seagate 425MB hard disk to get it to run and then I DID have a UNIX machine at home. Things were looking up!

It wasn’t until 1994 that I made my first steps in the “PC” world, picking up the bare bones of a 386SX machine and then sourcing the components to make a working system so that I could try out this new Linux thing and play with Microsoft Windows. Overall I think it cost me another £500 or so to get it running.

Still, it was essentially the end of the “boost phase” of home computing as far as I was concerned. At this point I had effectively, be it in primitive form, everything I have here today. I had a network (10Base2), UNIX and Linux machines, a Windows box and Internet connectivity (albeit via dial-up modem). From then on it was merely a case of a gradual improvement in speed and usability.

Until….

Enter the Age of the iDevice.

Yes, I can say that we have now entered a new phase of the computing story. It’s both a very good and a very bad thing.

Effectively, for me this was preluded many years before I got my first Apple when I got my Palm Pilot Pro and mobile phone (Motorola MR30 brick) in ’97. But it wasn’t really a revolution until I got my first smartphone in 2003, a Handspring (later Palm) Treo 600. It only had GPRS connectivity but it was e-mail on the go! It had limited web browsing. It was amazing at the time. (It also had amazing battery life as well, but that’s another story.)

But it wasn’t until I got the iPhone 3G that I really found how mobile connectivity should be. Simple, sleek, quick and it “just worked”. The iPhone 4 was just as good.

However, the bad thing about all these devices is the way that the iDevice simplifying of devices is starting to intrude onto the desktop (and laptop) devices. Locking the users out of being able to access and program them. It’s almost as if you’re only buying the privilege to hold and use the devices rather than own them. This is a potentially slippery slope.

Anyway, I’ve been rambling on for far too long now. So, I’ll conclude this piece and look forward to hopefully another 30 years of the odyssey to come. I think it’s going to be even more evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

[Edit: 7:50pm 12th November, 2011. : Replaced stock image of Sun 3/80 with image of my computer set-up in 1994 and 1995.]